[vc_row][vc_column icons_position=”left”][vc_column_text]There’s a much-touted refrain that employees leave managers, not companies. While that sentiment certainly holds truth, today’s reality is that job-hopping, even career-hopping, has become the norm for a younger generation of workers — even for those with good managers.

Recent research from staffing agency Robert Half found that some 64% of workers believe job-hopping to be an acceptable, even beneficial, practice — especially millennial workers. Millennials resign nearly two times as often as non-millennials with comparable tenure (34.5% compared to 19.4%), according to new data from people analytics company Visier. And when they do, most will give the customary two weeks’ notice, an arbitrary and mostly American phenomenon that increasingly seems antiquated.

This job-hopping mindset, combined with the inefficient standard of giving two weeks’ notice, can be an incredibly contentious and expensive problem for companies. How an employee leaves a company can also develop into an ongoing obstacle in an employee’s career, thanks to the increased use of backchannel reference checks.

While the job-hopping trend may be a difficult cycle to stop, there is a more useful, relevant, and less frustrating approach employers can implement that can not only decrease turnover, but also lead to mutually beneficial solutions for both parties. Leaders need to make discussions about career transitions and job opportunities less taboo in the first place.

For example, when Justin Copie, CEO and owner of Innovative Solutions, took over the company, he mandated that all employees interview elsewhere to see if the grass was greener. He only wanted people who really wanted to be there to stay, so he offered them an out. Once someone determined they actually wanted to stay, they were asked to help create their own job description to make sure that every aspect of their job personally resonated with them.

In a similar vein, CEO Josh Sample of Drive Social Media encourages his employees to discuss issues with him openly and to let him know if they want to do something else. For employees who are upfront and honest, he’s willing to help them find a new job and provides a recommendation letter while they wrap up their work at Drive.

Three years ago, our company, Acceleration Partners (AP), created our own version of an open transition program that we called Mindful Transition. What we and many other company leaders have found is that having an open transition program actually improves engagement, retention, and the culture overall.

What’s also important to understand is that transition discussions don’t have to end in an employee departure. For example, we recently had three people transition into new roles — moves that were made possible because of ongoing feedback and open conversations. This wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t felt safe talking to their managers and starting a discussion about their growing interest in doing something else.

Because they were a good fit for the open positions and we were made aware of what they wanted to do, we were able to consider them for those roles when they became available. This win-win situation is a perfect example of how an open transition program can help you retain high-value employees who might otherwise look elsewhere.

Setting the foundation

In our own experience, and in speaking with companies who have implemented similarly successful transition programs, there are four important components that need to be established in order for this type of program to work:

- A culture that encourages open and honest discussions between employer and employee without any fear of retribution, reprisal, or of being escorted out the door if they are forthcoming about being unhappy in their job.

- Training mangers on how to have “happy, present, and engaged” conversations with employees, and learning to spot and diagnose early signs of unhappiness or disengagement (more on this below).

- Having a clear framework for managers to understand which issues are fixable (and how to fix them), as well as which issues are not. This process and mindset are very different from the standard Performance Improve Plan (PiP) that most companies use today, which are often counterproductive.

- When the decision is made by the employer or employee to move on, there is a transition period that allows the employee to begin the search for their new job while remaining employed. During this time, the employee agrees not to give two weeks’ notice, and employers don’t ask them to leave right away (except in extraordinary cases).

Is an open transition program right for your company?

If you are a professional services firm with many client-facing employees, or if you have many highly skilled workers who are difficult to replace without heavily impacting your bottom line, then open transitions make the most sense for your company. Losing a client-facing employee often poses a big risk to client retention — and clients really hate account manager turnover. Having that employee engaged for a few months while you find their replacement can be really helpful in making a smooth transition.

However, if you operate in an industry or company where talent is in high supply, and the impact of turnover on your business might be low, you might not need or want to fully embrace all aspects of this approach. For example, if you have a call center with 100 people who perform exactly the same role, and their roles are fairly plug-and-play, then a full open transition program just might not make as much sense. I don’t want to imply that culture and people are not important in this example, however, there is objectively much less of a risk to business continuity.

As mentioned earlier, your company’s culture will also play a deciding role. If employees don’t feel like they can trust management, and if open communication and respectful outcomes aren’t a priority, a program like this will be unlikely to work within your company and may do more harm than good.

Launching the program

If you feel that your organization is ready to move away from the practice of giving two weeks’ notice, while simultaneously creating a culture that retains good employees, here are a few things to implement so that your employees will feel comfortable and confident with this type of program:

1. Establish your transition program during onboarding

It’s important to begin discussing how you expect people to depart from your company early in the employees’ hiring process, even as early as in recruiting, or during their new employee onboarding period. The reason to have these discussions at the outset is that an important part of being a transparent company is making new employees aware that you have a safe and productive exit strategy in place. You want them to know that in the event that the job doesn’t work out, or if they come across a great opportunity at another company at some point, it won’t end in disaster for their career. This seemingly paradoxical approach actually makes your company a less risky bet for the employee.

2. Have “happy, present, and engaged” conversations regularly

The data clearly shows that if an employee is not happy or engaged, it’s likely to be reflected in their performance. Whether it’s during their weekly or bi-weekly one-on-one’s, their quarterly check-ins, or during a general conversation, a great way to initiate these discussions is to ask employees three questions: Are you happy? Are you present? Are you engaged? The answers to these three questions can offer a window into whether an employee is bringing their whole self to work. It can also serve as an early warning detection system for potential problems and unhappiness.

By not waiting until someone is unhappy, you can take a lot of emotion off the table. This also makes it easier for the employee to hear what you’re saying because strong feelings and broken trust aren’t getting in the way of facts.

While it’s ideal to have these “happy, present, engaged” conversations frequently, for many companies, just having them at all would make a significant impact. The recommendation is that managers be encouraged to have them more formally — at least quarterly. Regardless of the frequency, these conversations should take place immediately after an issue first bubbles to the surface to prevent it from festering.

Another tactic that can support early detection of engagement issues is to ask team members what you as a company or as a manager should start, stop, and continue doing. This question can help identify trends that impact employees’ happiness across the board. As an example, this start-stop exercise revealed that our global client onboarding process was a source of stress for several employees, so we introduced changes to improve it.

3. Train managers and leaders on how to give and receive feedback

The ability to give and receive feedback is not only a vital skill in and of itself, it’s also closely tied to millennials’ job satisfaction. A 2016 Clutch HR survey found that 72% of millennials whose managers provided accurate and consistent feedback said that they were happy and fulfilled in their job. Conversely, when their managers didn’t provide accurate and consistent feedback, only 38% reported being happy and engaged.

To both hold your managers accountable and ensure that they know what it means to encourage and welcome difficult conversations, it’s important to hold regular training sessions on how to give and receive feedback.

Regular feedback conversations lay the foundation for an employee to feel safe about telling their manager when they are no longer happy or engaged, or that they’re looking to make a job change. While it’s not always easy to hear, at the very least, it gives a manager a heads-up that someone might have a foot out the door.

4. Don’t let problems fester

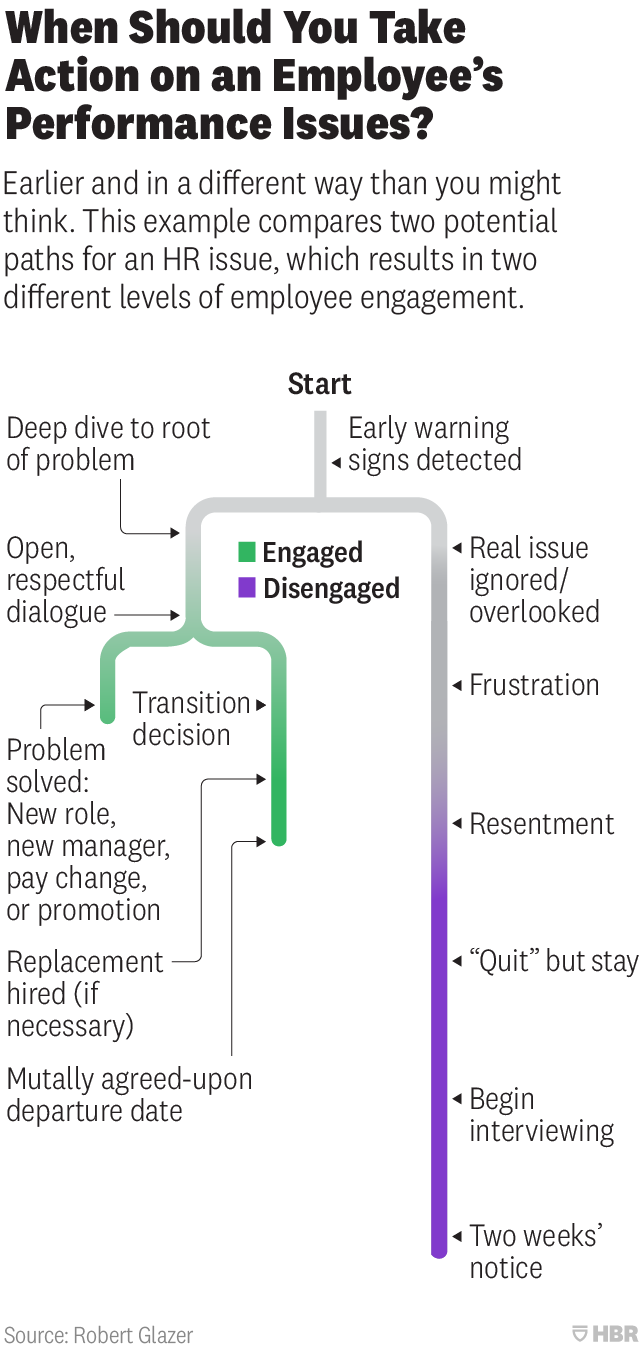

When you encourage both employers and employees to engage in open conversation and to take those conversations much deeper, a fundamental timeline shift occurs in the typical path of disengagement.

For example, let’s imagine that the decision has been made to part ways with an employee due to persistent performance issues. The reality is that the first signs of those performance issues were likely appearing many months, even years, earlier. That would have been the appropriate time to start the “happy, present, engaged” conversations.

This chart shows how a performance issue can either be addressed and resolved in a short period of time or develop into disengagement. At that point, the situation will be past the point of no return.

What often happens is that by the time someone gives their two weeks’ notice, it’s too late; they are mentally already out of the door and disengaged. As most employers can attest, the most dangerous employees aren’t the ones who leave, but the ones who “quit and stay.” They are physically present, but mentally already gone.

If you can identify and address the issue early on — even if the consensus is that this work partnership is just not going to work out — you can at least be working toward a mutually beneficial outcome while helping to ensure that their engagement remains high during the transition.

Most managers who value open communication and want to develop trust with their employees would much rather have these honest discussions and try to resolve issues than have problems fester in secret, or have people on their team furtively looking for a new job during work hours and then giving two weeks’ notice at an inopportune time.

What happens if someone gives their two weeks’ notice anyway?

Although the ideal is to cultivate a culture of open, respectful communication where everyone feels safe saying when they are unhappy, not present, or not engaged, the reality is that there will always be employees who revert to the standard two weeks’ notice. If your company has not made it safe to have these discussions and has not created a culture that encourages open conversations or transitions in a different way, employees won’t and shouldn’t do anything differently than they do today.

Why should they tip their hand or open up about their dissatisfaction if they are penalized for that behavior? Behaviors follow incentives. To get different results, you have to fundamentally change the game and reward the behavior you seek.

Openly acknowledging that your company might not be the best fit for everyone long-term allows you to completely change your dialogue with your team members. When employees know they can honestly discuss their career goals — and even professional unhappiness — employees of all generations are not only more likely to stay, they’re more inclined to do their best work and care as much about what’s best for your company as they are about their own career path.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]